Hong Kong Headaches

An icon of globalization falters

Like many others, I’ve observed developments in Hong Kong—once the crown jewel of cosmopolitan Asia—with a combination of concern and disappointment. Along those lines, this story from Nikkei last week caught my eye:

Hong Kong has logged its biggest fall in a global ranking of cities' ability to attract people, business and capital, due largely to COVID-19 headwinds and deteriorating economic freedoms.

The Asian financial hub slipped to 23rd place in the latest Global Power City Index, down from 13th last year. The number of arrivals and departures at airports in Hong Kong has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels, hurting the city's score on accessibility. By contrast, the number of air travelers going through other hubs, such as New York and Chicago, has increased sharply from the previous year.

Hong Kong also lost points for its worsening economic freedom, leading to a drop in its ranking in the index's economy subset. Hong Kong ranked fifth in economy in 2021 but plummeted to 28th this year amid rising concerns over the strict zero-COVID policy and China's growing political clout in the city.

The rankings plummet reaffirms what’s been obvious for some time: the past four years have been the single bleakest period since the 1997 handover. Hong Kong today, as with Mainland China, is suffering a massive international image problem; one rooted in its failures to adequately address, much less resolve, multiple political and governance crises. It remains unclear (and in my opinion unlikely) that the city ever regains its pre-2019 swagger.

The HK backstory

For decades—first as a British colony and later as a PRC special administrative region—Hong Kong served as a barometer for globalization writ large; its allure rooted in its openness and strategic position as an “edge” city straddling and connecting the Sinosphere with the Western world. A bastion of financial freedom, rule of law, stability, (relatively) good governance, and international connectivity, the city proved a vastly appealing place to do business during an epoch defined by China’s integration into the global trading system. As the FT writes: “The emergence of Hong Kong as a financial centre was built on two open gates: one connecting it to China and the other to the rest of the world. Trust in the fairness of its legal systems and the free flow of information put it on a footing with London and New York.”

Source: BIS

Ambassador Kurt Tong, who served as former US Consul General and Chief of Mission in Hong Kong, astutely summarizes this “secret sauce” as such:

Being physically and economically close to China has of course been a necessary ingredient in Hong Kong’s economic success. But the city’s most important strengths stem from its differences with China. Until this year at least, Hong Kong has been widely recognized for its strong rule of law, respected independent judiciary, and technocratically sophisticated yet still laissez faire governance traditions. The city’s low income taxes, zero tariffs, lack of corruption, sound infrastructure, and fluid labor markets all stand out as anomalies in the Chinese context, and have earned Hong Kong consistently high global rankings for openness and competitiveness. The foundation for all of these pro-business policies — as well as the personal freedoms that Hongkongers have enjoyed — has been Hong Kong’s common law traditions and its legal separation from China.

It’s pretty clear that Hong Kong's multi-decade success story was rooted in an ability to navigate the knife’s edge between preserving a high degree of autonomy, openness, and cultural uniqueness on the one hand while deepening economic, political, and interpersonal enmeshment with the People’s Republic on the other.

Sadly, however, those halcyon days seem well and truly over. The past four years degraded the city’s unique advantages and raised probing questions about its future viability as a global business hub. After 25 uninterrupted years atop the Heritage Foundation’s annual Index of Economic Freedom, Hong Kong was notably removed altogether from the 2021 rankings, with the think tank noting that “the loss of political freedom and autonomy suffered by Hong Kong over the past two years has made that city almost indistinguishable in many respects from other major Chinese commercial centers.” Asian rival Singapore now sits at the top spot.

I believe three critical developments punctuate Hong Kong’s anni horribiles:

First, we have the 2019 protests, which grew out of public hostility towards a proposed PRC extradition treaty and then quickly snowballed into mass-scale demonstrations calling for comprehensive reforms. That movement brought millions out to the streets, exposed long-simmering tensions within Hong Kong society, and reflected visceral anger over China’s creeping encroachment on the city’s political sovereignty and cultural identity.

By openly challenging and repudiating the legitimacy of “the system”, the protest movement brought about Hong Kong’s worst political crisis in decades; serving up an optical disaster for (then) HK Chief Executive Carrie Lam, Xi Jinping, and China’s Communist Party. Dan Harris, a leading authority on Chinese commercial law, noted at the time that “Hong Kong as an international business and financial center is no more.”

Next up: the subsequent crackdown—underpinned by the harsh, PRC-imposed 2020 National Security Law (NSL)—which effectively banned peaceful protests, created an environment of pervasive self-censorship, defanged the city’s pro-democracy camp, and decimated Hong Kong’s civil society through a campaign of intimidation, mass arrest, and police brutality. In short order, Beijing fully subordinated the independence of key Hong Kong institutions—the electoral system, media, judiciary, bureaucracy, and education sector—to its will while strengthening control over the city’s internal affairs.

Human Rights Watch captured this “new normal” in a 2021 report entitled “Dismantling a Free Society”:

Basic civil and political rights long protected in Hong Kong—including freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly—are being erased. It is evident that the NSL is an integral part of Beijing's larger efforts to reshape Hong Kong’s institutions and society, transforming a mostly free city into one dominated by Chinese Communist Party oppression.

As does Keith Richburg, director of Hong Kong University’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre, in this WAPO opinion piece from last summer:

In 1997, many people here assumed that after 25 years, mainland China would look more like Hong Kong — more liberal and far less anchored by archaic-sounding Communist Party ideology. As China grew richer and more globally connected, the thinking went, the country would become more democratic and open to the world.

What happened instead has been the opposite. In 2022, Hong Kong looks more like China — repressive, intolerant of dissent, suspicious of foreigners and bent on indoctrinating the entire population with an enforced loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party and its whitewashed view of history.

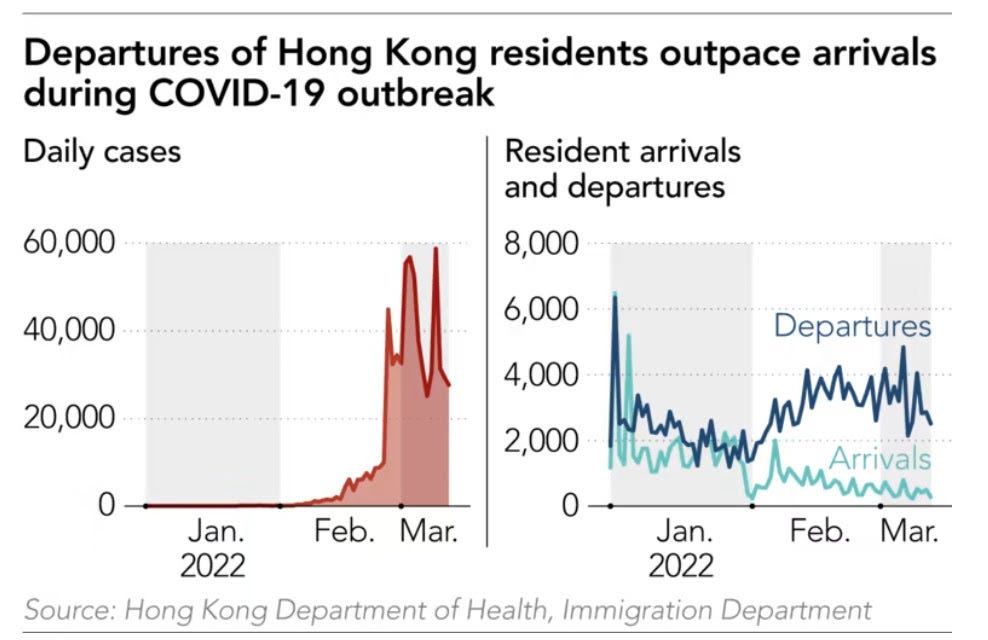

Finally, Hong Kong’s COVID-19 response, modeled on China’s draconian (and now scrapped) zero-COVID protocols, seemingly achieved the worst of all worlds. On the one hand, stringent travel restrictions, mass testing requirements, and quarantine control measures effectively severed—albeit temporarily—the city’s connection cords to the international community. On the other, the underlying policy approach—paired with an inability to adequately vaccinate the elderly—failed to prevent a massive case spike in the face of the hyper-transmissible omicron variant; overwhelming the city’s public health infrastructure and temporarily resulting in the highest per-capita death rate in the world.

Source: Nikkei

I think the upshot here is this: taken together, the protests, crackdown, and COVID handling introduced unprecedented levels of political risk to Hong Kong; sending its economy into recession in 2019 and 2022, tanking the city’s once-sterling global reputation, and provoking a record drop-off in population level amidst an exodus of expats and HK nationals.

Different Narratives

I want to hold here on what I think is a crucial point: a primary reason why the issues at play are so intractable is the chasm in both diagnosis and prescription between what Chinese officials (and their HK subordinates) see when looking at the city versus what many HK residents and outside observers see. Simply put, the contrasting “big narratives” around what ails the city are diametrically opposed and mutually exclusive:

I would argue the root cause of Hong Kong’s problems stems from Beijing’s overbearing authoritarianism and compulsive, paranoiac need for control. In subordinating Hong Kong’s unique attributes—its distinct cultural identity, openness, rule of law, and global connectivity—to the prerogatives of China’s security state, HK is being unhappily reduced to “just another Chinese city”; in turn, provoking widespread animosity and undermining its luster as a business hub.

According to this worldview, the underlying conflict is about power, representation, and repression. Hong Kong is not ruled in accordance with the will of its people, and they lack the ability to affect change. The loci of control run through Beijing. Stringency is the root of the problem.

That is not, to put it mildly, how China’s political elite see matters. As Andrew Nathan points out, Beijing believes it “treated Hong Kong with a light hand”— granting it special economic privileges and excessive autonomy that eventually snowballed into a national security threat.

In this worldview, leniency is the root of the problem. The city’s colonial past and the lingering influence of Western “universal” values drive socio-political tension, creating an environment where, per Nathan, “Western powers, especially the United States, have sought to drive a wedge between Hong Kong and the mainland.” In this viewing, forcing the territory ever more closely under the umbrella of the Chinese security state is required to stamp out nefarious foreign influence, tamp down social polarization, and ensure the public’s loyalty to the People’s Republic.

It’s also noteworthy that the protest movement achieved some fleeting wins: Carrie Lam eventually withdrew her unpopular extradition bill, and HK’s pro-democracy camp ran up landslide victories in November 2019 local elections. Those victories, however, were overshadowed by what came next. Beijing held the trump cards. It never panicked, countenanced democratic reforms, or lost its grip on Hong Kong‘s political class, business elite, and police force. In short, the Communist Party’s narrative prevailed and its “solutions” were imposed on the city—with the overt backing of powerful local constituencies—in the form of strict political controls, rigid “patriotic” education reforms, and zero-COVID. Despite their protestations, foreign governments could not meaningfully prevent or penalize Beijing from cracking the whip.

I don’t find it surprising that the economic and reputational damage suffered by both China and Hong Kong was deemed a price worth paying in the name of preserving control and avoiding a humiliating step-down in the face of bottom-up social pressures. The rubber-stamp “election” of unapologetically loyal apparatchik John Lee—renowned for his unabashedly hardline approach in stamping out the 2019 protests and then weaponizing the NSL to crush HK’s pro-democracy camp—to the position of Chief Executive reaffirms this new normal; Xi Jinping’s “securitization of everything” style of governance is now firmly entrenched as Hong Kong’s political reality.

Two Takeaways

One: for decades, Beijing operated on the assumption that increased “contact” with Hong Kong (and Taiwan)—in the form of closer people-to-people exchanges, tourism flows, investment dollars, and overall economic integration—would facilitate a common “Chinese” identity, smooth over intense political differences, and pave the way for both territories’ seamless integration into the People’s Republic.

Today, that working hypothesis lies in tatters. In both instances, exposure has not bred fondness but resentment. China’s autocratic trajectory and heavy-handed, alienating approach to both Hong Kong and Taiwan only strengthened powerful local identities and drove both citizenries to reject the Communist Party’s political values and national mission.

Source: Economist

Zooming out a bit, we see this story playing out across the free world. I find it extremely striking that within the liberal democratic camp, the locales most intimately affected by China’s rise (Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, USA) have seen plummeting public attitudes toward the country. Not only has connectivity and contact failed to mitigate tension, but technological, financial, and commercial linkages have become powerful drivers of geopolitical conflict.

Two: Hong Kong’s position feels increasingly precarious due to broader changes in the global macro order which cut against the general atmosphere of openness and transnational connectivity under which the city thrived over the past 30-plus years. I’ll quote a few experts here to reinforce my view that we’re seeing a step change in the global trade and security order unlike anything experienced in decades:

Nouriel Roubini (MegaThreats): “We are facing a regime change from a period of relative stability to an era of severe instability, conflict, and chaos.”

Alicia García Herrero (Bruegel): “After decades of increasing globalization both in trade, capital flows but even people-to-people movements, it seems the trend has turned towards deglobalization.”

Mark Leonard (Politico): “Hyper-connectivity is not only polarizing societies into competing filter-bubbles and creating an epidemic of envy, it is also providing a new arsenal of weapons for great power competition. Countries are now waging conflicts by manipulating the very things that link them together.”

I see several hallmarks of this new era. Taken together, they carry serious transmission risks which threaten Hong Kong’s position as a major financial center and a beacon of neoliberal globalization, namely:

-a reinvigorated emphasis on protectionism and industrial policy; from Beijing and Tokyo to DC and Brussels.

-an escalating Sino-American rivalry and the return of great power politics that now touches on virtually every facet of the bilateral relationship and permeates the entire global trade and security order.

-surging techno-nationalism, embodied by stringent controls on the flow of capital, people, data, and technology across national borders; once again primarily between the People’s Republic and the US and its allies.

-an ongoing reappraisal of global supply chains, with an increasing focus on resiliency over efficiency and a related emphasis on the localization and “friendshoring” of manufacturing capacity—particularly around strategic industries like semiconductors and electric vehicles.

-an increasing reliance by the US (and its allies) on a sprawling toolkit of economic and financial sanctions—despite their mixed track record of success—in attempting to shape desired geopolitical outcomes.

-the ever-growing threat of existential climate catastrophe, which now exerts significant pressure on the operation of global supply chains and capital markets alike.

-and, most alarmingly, the growing risk of armed conflict breaking out in the region; whether over the Taiwan Strait or the Korean Peninsula.

I’ll be blunt: the political risks of doing business in the Hong Kong have risen considerably over a (very) short time horizon. Foreign firms now struggle to attract and retain personnel in the wake of zero-COVID program. Many businesses are contemplating downsizing or exiting the territory altogether. The Guardian notes that “since Beijing imposed the national security law in the summer of 2020, executives say there has been a growing sense of uncertainty among businesses, both local and foreign.”

Hong Kong, China, and the world in an irrevocably different place than during the city’s heyday. Many critical factors undergirding its success are degrading, or simply no longer present. While the city retains crucial geographic and legacy advantages, it strikes me as ill-suited for the transition from an era defined mostly by openness and connectivity to one marked by tightening political controls, trade wars, deglobalization, and boiling great-power competition.